The Core Logic Behind Electrolyte Formulation Development

An Engineering Perspective on Performance Trade-offs

Electrolyte formulation is often described as a process of “adjusting solvents and additives to find the right ratio.”

In practice, however, formulation development is far less about mixing ingredients and far more about engineering trade-offs between competing performance requirements.

This is why electrolyte formulation should be understood not as a trial-and-error exercise, but as a structured engineering decision process.

What Is Electrolyte Formulation Development Actually Solving?

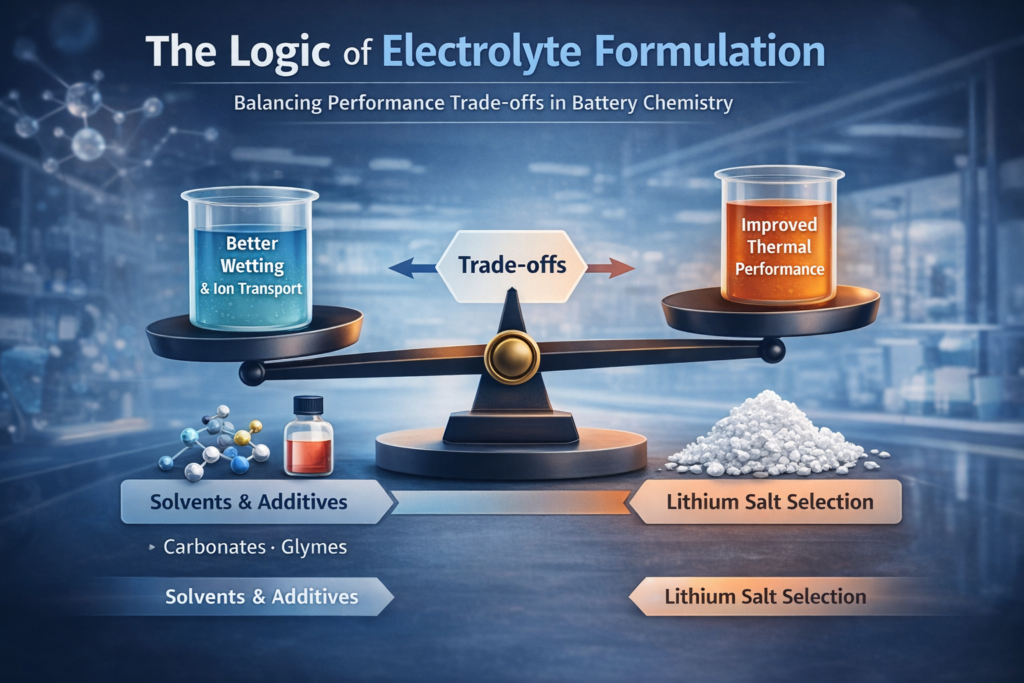

In real laboratory environments, electrolyte performance metrics rarely improve in isolation.

For example:

- Improving electrolyte wettability typically requires lowering solvent viscosity, which may compromise high-temperature stability.

- Enhancing high-temperature performance often involves higher-boiling solvents, which in turn increase viscosity and reduce ionic transport.

- Suppressing gas generation or parasitic reactions may introduce higher interfacial resistance.

As a result, every formulation exists at the intersection of multiple conflicting requirements.

The goal is not to maximize a single parameter, but to identify an acceptable balance under defined operating conditions.

From this perspective, formulation optimization is not simply “adjustment,” but prioritization—deciding which properties are critical, which are secondary, and which trade-offs are acceptable for a given application.

A Typical Example: Low-Temperature Performance in Fast-Charging Cylindrical Cells

Consider electrolyte development for fast-charging cylindrical cells with improved low-temperature performance.

- Introducing ester-based solvents may enhance low-temperature ionic transport, but often reduces high-temperature stability.

- Additional high-temperature additives may recover thermal performance, while increasing interfacial resistance.

- Further adjustments may shift rate capability, impedance, or cycle life in different directions.

At this stage, formulation work is no longer about “adding more components,” but about defining performance priorities:

Which parameters must remain fixed, which can be adjusted, and which compromises are acceptable. This reflects the fundamental logic of electrolyte formulation:

not mixing, but weighing trade-offs.

From Ingredients to Functions: The Core Design Logic of Electrolytes

Electrolyte properties arise from the functional combination of its components, rather than the presence of any single material.

Typical examples include:

- Cyclic carbonates: higher viscosity, strong lithium salt dissociation capability

- Linear carbonates: lower viscosity, weaker salt dissociation

- Fluorinated carbonates: improved oxidative stability and interfacial energetics

Formulation development, therefore, is a process of reconstructing functional balance through molecular structure selection.

When components are added or adjusted:

- Increasing low-viscosity solvent fractions alters transport behavior

- Additives reshape interfacial reactions and suppress side processes

- Higher salt concentrations modify solvation structures and lithium-ion transference numbers

Although this may appear as “adding materials,” the underlying action is actually redistributing functions within the system.

Experienced formulation engineers do not ask “What should I add next?”

Instead, they ask:

Under which conditions, at which scale, and in what manner should each component exert its function?

Why Electrolyte Formulation Is an Engineering Problem, Not Just an Experimental One

Electrolyte development spans multiple scales:

- Molecular structure

- Interfacial chemistry

- Bulk transport properties

- Cell-level performance

As such, formulation is best understood as an engineering process that integrates macroscopic performance targets with microscopic structural control.

This is also why simply copying an existing formulation often fails when applied to a new system.

Without understanding the underlying structure–function relationships, formulations become recipes rather than designs.

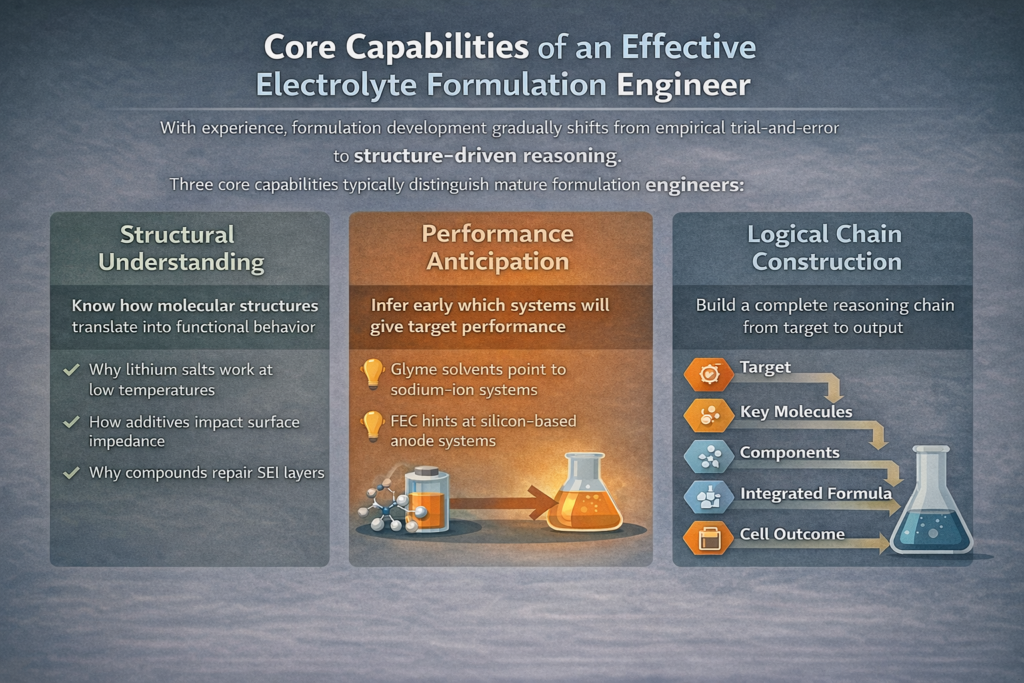

Core Capabilities of an Effective Electrolyte Formulation Engineer

With experience, formulation development gradually shifts from empirical trial-and-error to structure-driven reasoning.

Three core capabilities typically distinguish mature formulation engineers:

1. Structural Understanding

Engineers must recognize how molecular structures translate into functional behavior.

For example:

- Why certain lithium salts exhibit superior low-temperature performance

- How specific additives influence interfacial impedance

- Why some compounds improve long-term cycling stability through SEI repair mechanisms

When structure becomes interpretable, formulation behavior becomes predictable.

2. Performance Anticipation

Structural understanding enables early performance inference:

- Certain solvent systems suggest compatibility with sodium-ion or hard-carbon anodes

- High concentrations of specific additives often indicate silicon-based anode systems

Formulation development then becomes hypothesis-driven rather than blind adjustment.

3. Logical Chain Construction

Advanced formulation work follows a consistent reasoning chain:

Target performance → Key structural elements → Candidate component systems → Integrated formulation → Cell behavior The more complete this chain, the more robust and transferable the formulation outcome.

Improving Formulation Skills: Practical Perspectives

Electrolyte formulation is ultimately a language of structure and function.

Improvement requires more than testing materials—it requires building conceptual clarity.

Practical approaches include:

- Analyzing additive structures and functional groups

- Studying failure cases to identify mismatched functions

- Expanding perspectives into surface science, physical chemistry, and polymer science

- Systematically mapping structure–property relationships across projects

Over time, isolated knowledge points become a coherent internal framework.

Concluding Remarks

Electrolyte formulation development is a system-level design process, bridging molecular structure and engineering performance.

Its core question is not “What changed after adding a component?”,

but “How did a specific component alter a specific function under defined conditions?” When this logic becomes clear, formulation work moves beyond adjustment and becomes intentional material design—a principle equally relevant to electrolyte systems, electrode materials, and full-cell engineering.

Other Blog Posts You Might Like

Nanomaterials: The Invisible Forces Reshaping Our World

Invisible, Yet Invaluable: A New Era of Materials In the quiet folds of everyday life,…

Read moreEvent Recap: Future Development of Lithium-Ion Batteries – From ICAMEEH 2024

From September 24 to 27, 2024, we are honored to be the industrial exhibitor of…

Read moreCompany insight: Strengthening capability Through Strategic Partnerships

At ANR, our commitment to innovation and excellence is driven by the quality of our…

Read more